When I was six years old, my parents got divorced. They sat David and I down in the living room, a classic 70s set up: shag carpet, chocolate brown “suede” sectional sofa, back-lit wall unit with built-in bar, and told us that our dad would be moving out. I see this scene like some sort of Noah Baumbach movie playing in my head: I remember something along the lines of “it’s not you, it’s us.” After the talk on the couch, he walked out through the front door. He left. Was there a suitcase at the door the entire time we were talking? I can’t recall.

I do remember the hot intensity of fear, uncertainty, and sadness. Would my father still love me? Would he leave and never come back? Would he get remarried and forget us? Would he still be so angry all the time? All reasonable questions for an insecure six year old who had watched her father implode over and over again inside the four walls of her home.

But this is not a story about divorce, really. It is the story of how I fell in love with restaurants. And that started when my father moved out and realized he could not cook.

It was 1975 when my dad first moved to an apartment in Queens. Then in 1977 he moved to the Upper East Side, to a place on East End Avenue that was convenient to the FDR and the Triboro Bridge so he could quickly fetch us from Queens where we lived full time with my mother. The custody arrangement was this: we saw him every Tuesday for dinner and every other weekend.

What this meant was on Tuesday evenings he picked us up (and later when we were old enough we took the F train to Lexington Avenue and 53rd Street) for dinner in the city. My father was a cancer surgeon and fairly busy, and he didn’t know how to cook much of anything. When we ate at his house on weekends, there were a few meals on rotation: he was great at omelets (all dads are good at eggs it seems), but his steaks were singed until gray and the texture of the sole of your dress loafers; slabs of meat that were habitual choking hazards. His chicken cutlets were actually pretty good, and I loved watching him make them, dipping them in the egg and then the breadcrumbs and then into the hot oil.

With every meal, there was one stalwart side dish: Stouffer’s Spinach Souffle, a fluffy creamed spinach casserole that he kept in stacks in the freezer, unboxed, and baked in the oven (never microwaved) so that it was puffed up and developed a little dark green crust, the color of moss. It was creamy and cheesy, with just a nudge of vegetal flavor, a taste that was sort of spinach adjacent. Gosh, I just loved that Spinach Souffle. Along with the gorgeous Persian meals my Bibi cooked, the fish and chips my mom made after my ballet class every Wednesday night in her countertop Fry Baby, and the frozen yogurt at Alexander’s, it is one of the defining foods of my childhood.

The point though, is that while Dad did try to cook, mostly he took us out to eat. We were restaurant kids.

We ate mostly at local diners and neighborhood restaurants: The Mansion on the corner of 86th Street, The Green Kitchen lower down in the 70s on First Avenue close to his girlfriend at the time, and Rupert’s, a casual spot on the Upper East Side. On Tuesdays, when he’d pick us up at the F train for dinner, we would go to The Metropolitan Cafe, a breezy bustling American bistro on First Avenue in midtown that I remember being full of grownups in suits who seemed very busy and very important.

I remember my go-to meal was Angel Hair Pasta Primavera, something that I felt was quite sophisticated and also delicious at the same time. But one evening my dad ordered something for me and David to try. It looked sort of like a pile of chicken nuggets and when I asked my dad what it was he said, “It’s chicken. Try it.” When my dad said “try it,” you listened, and so I tried it, and, thankfully, it was damn good: delicate, salty crispy little nuggets and squiggles that tasted great dipped in a pulpy marinara sauce that it came with.

A few bites in, he told us it was fried calamari. I was slightly horrified that I had eaten squid, but then it sort of made sense, those squiggly bits were not exactly in the shape of any chicken I’d ever seen. I never stopped loving it. We joke about how he got us to try squid to this day.

But the most impressive meals of my youth were not at the local spots, they were the fancy restaurants he took us to. My favorite was Maxwell’s Plum, a place that felt like a fantasy world secreted behind closed doors: a dramatic, darkened room lit with candles and filled with life, laughter, and gaggles of glamorous, fancy people leaning into each other, smoking and drinking, looking like they had everything they could ever need.

There were three of us, seated at a table for four, but it didn’t matter. I didn’t think about the extra seat, not filled by my mother. I was too distracted. I loved the servers, in their starched white shirts, dinner jackets, and bowties, who were so kind and friendly and took care of everything and made you feel loved. I remember the pretty helium balloons they tied to the backs of our chairs, and getting lost in the reflection of the emerald and ruby stained glass window that hung from the ceiling, and waiting for the flaming Baked Alaska that toured the dining room on a golden cart on wheels to make its way to our table for dessert. An ice cream cake, wheeled to your table, covered in meringue, and then set on fire! What could be better? This was heaven.

And then there was Rumplemeyer’s, in the St. Moritz Hotel on Central Park South, with its pink walls decorated with Egyptian-style mosaics, hot fudge sundaes and hot cocoa, served in silver pots at round tables covered in soft white linen. I remember there was a sweet little shop at the front selling gifts where my dad bought me a small Koala teddy bear with a little pouch that held its baby. I loved that koala and the way the little baby was always safely tucked inside.

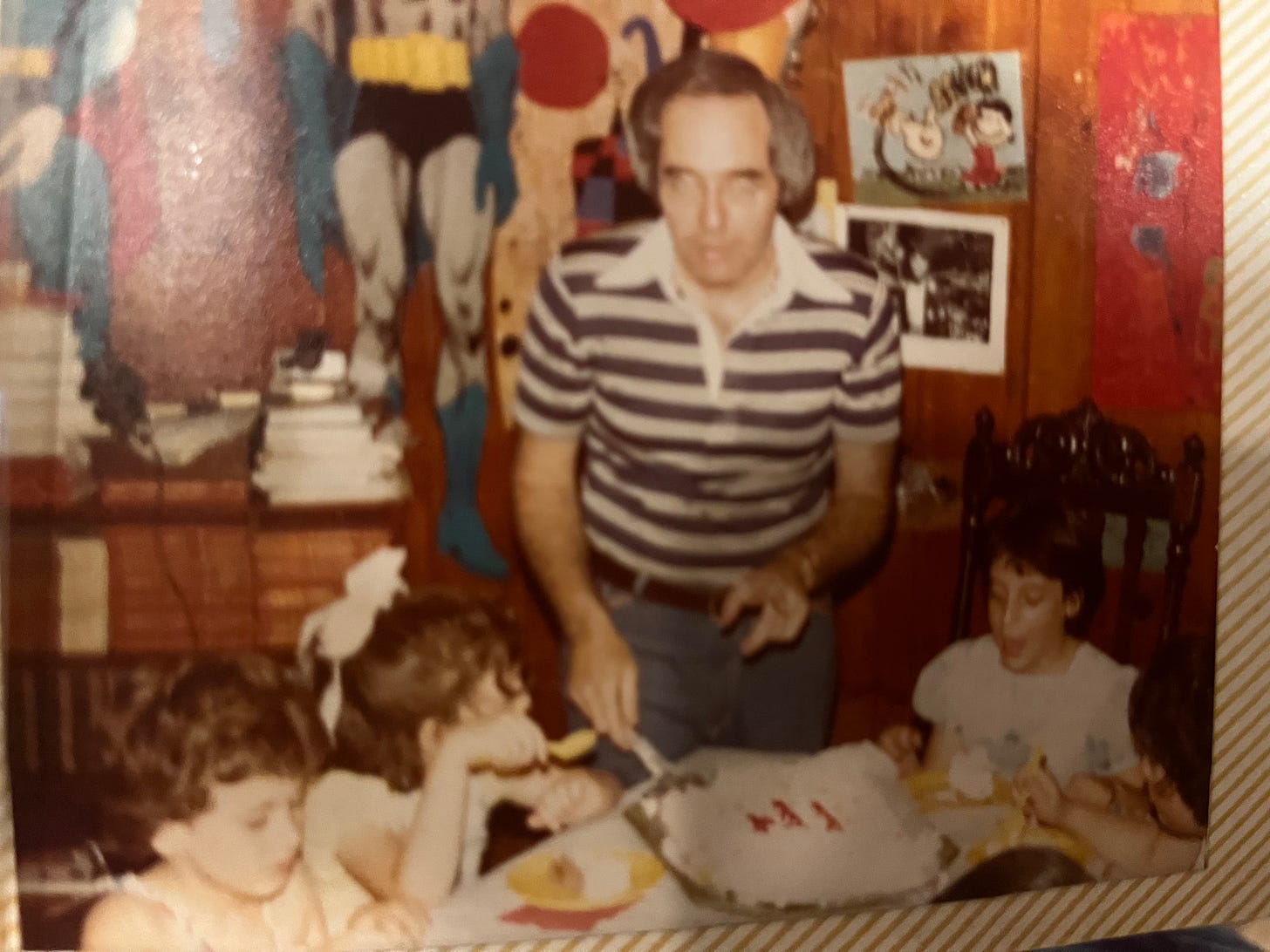

He took us to Serendipity for Frozen Hot Chocolates, to The Russian Tea Room for Chicken Kiev, and to The Boat House for lunch after hot days in Central Park. We went to the Rainbow Room in Rock Center and Windows on the World on our birthdays, and when we went to the theater, which we did a lot thanks to my dad’s love of Broadway (I saw a Chorus Line three times!), we would go to Barbetta’s or Victor’s Cafe, Joe Allen or Sardi’s. I was small enough that my feet did not touch the floor at many of these places, but there I was, sitting next to my dad.

At some point I realized, those tables, scattered across the city, became some form of home. The diner booth at the Green Kitchen is where we tried to find a way forward after the divorce, where we tried to connect with my dad, who was broken himself. We did not have emotional stability as kids; my father could not give us that when we were young, he was raised by wolves himself, and he was too damaged. But I know he loved us, and still does. I know he tried to be better than he was. He gave us all he could of himself, and when I consider it now, I think what he couldn't give us, perhaps he gave us through restaurants.

At tables across the Upper East Side, we created some form of a three-person family. At restaurants, we figured out how to get through it. There was joy in hot stacks of diner pancakes, and we made memories, good ones, in baskets of fried calamari, and in ice cream cakes set ablaze on a cart on wheels.

He gave us the theater of dining, the thrill of eating out, and the security of hospitality—of a warm hello, a sweet goodbye, the endless loop of “can I get you anything sweetie?”, and the impossible joy of a balloon tied to the wrist of a child.

Andrea, your writing is a feast.

Love this one! Such vivid memories.